Amnesty International has received numerous reports of ill-treatment of foreigners in Japan. Some of the victims are prisoners serving a custodial sentence or suspects held in police custody or pre-trial detention centres. Others are asylum-seekers detained in Immigration Detention Centres pending a decision on their claim to asylum, or foreigners who are illegally on Japanese territory and are detained pending repatriation.

Those alleged victims of ill-treatment who wish to remain anonymous are referred to in this document by initials or pseudonyms. Some of the victims have initiated legal proceedings against those responsible for alleged ill-treatment; information about these proceedings is given where appropriate.

“When you leave Tokyo Detention Centre you are not a human being. If you have a dog in your house you don’t treat it like this....They do terrible things - I will never forget what they did to me as long as I live”. “A”, interview with Amnesty International

Two foreign inmates of Tokyo Detention Centre have lodged appeals for state compensation on the grounds of having been subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment during their detention. Both appear to have been targeted for ill-treatment because of their foreign nationality (see below case of “B”, a Nigerian national).

The Tokyo Detention Centre mostly houses inmates who are awaiting trial. It also holds prisoners under sentence of death. “A”, an Egyptian prisoner, told Amnesty International that he was the victim of a series of assaults between November 1993 and August 1994. Soon after entering Tokyo Detention Centre, “A” was accused by a guard of breaking an internal rule by talking at an inappropriate time. As punishment, he was thrown into a “special cell”, in which he was under 24-hour video surveillance by prison guards. This cell was in a particularly smelly and unhygienic condition. He claims that the cell was infested with insects, the floor was covered in dust, and filth remaining from the previous detainee was piled up in the corners of the room. Having been kept in these conditions for several days, “A” began to develop skin problems and after his release from the cell, he had to go into hospital for two months for treatment.

Keiheikin is a form of administrative punishment in Japanese prisons whereby detainees are forced to remain motionless in a kneeling or crossed-legged fashion in the middle of a single cell for hours on end for a period of up to two months. Detainees are not allowed to do physical exercise, take baths, meet people from outside the prison, or write letters.

On coming out of hospital, “A” claims that he was punished with a further 15 days of keiheikin (“minor solitary confinement”). During the keiheikin period, “A” was made to remain motionless for several hours each day. There was no exercise outside the cell, and only about 15 minutes exercise, inside the cell, twice daily.

Aerial view of Tokyo Detention Centre. Note the small outdoor exercise areas laid out in the shape of fans at the end of the cell blocks (bottom and centre right). © Kyodo Press

Following this harsh treatment, “A” launched a state compensation suit. However, he claims that in March 1994, just before his case was due to be heard in court, he fell victim to further ill-treatment. He alleges that he was rebuked by a guard for using some string to tie up the papers concerning the legal proceedings he had initiated. When he tried to explain that he had been given the string by another detention official, the guard allegedly replied: “Don’t take us Japanese for idiots”. “A” claims that the guard then called about 15 other guards to the scene, who proceeded to kick him all over his body and on his face. “A” claims that the original guard participated in the physical assault by stripping him naked, kicking him hard in the abdomen and forcibly thrusting a prison truncheon up into his anus.

Afterwards, “A” was taken again to a “special cell”. He alleges that the guards who took him there continued to torment him by pulling his pubic hair. “A” was reportedly kept naked in this second “special cell” (which he said was dirtier than the first) for a period of three days. “A” claims that as a result of this violence he sustained a number of serious

injuries including internal and external bleeding and hearing loss in his right ear. His lawyer has stated that after the attack, one of his teeth could be seen sticking out over his lower lip. It appears that “A” was taken out of the “special cell” on the advice of a prison doctor who warned that he would die if left in those conditions.

“A” made a formal complaint about his treatment in March 1994. Four months later, in July 1994, he underwent a medical examination on the order of the Tokyo District Court. The state of his injuries was fully recorded including the bloodstains on his trousers and on the guard’s trousers. Photographs were also taken of the insects that infested the first “special cell”. However, the court refused to send judicial officials to inspect the cell itself or to request the Detention Centre to submit “A’s” medical records.

The hearing into “A”’s case for state compensation began in November 1994. At the same time, he also lodged a criminal complaint to the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office against 16 guards from the Detention Centre, accusing them of abuse and violence. However, the Public Prosecutor decided to drop the case in July 1995 despite the July 1994 medical evidence suggesting that violence had occurred. “A” made an immediate appeal to the Tokyo District Court for a re-examination of his complaint but his request was turned down after two weeks, on the grounds that there was no cause to question the decision of the prosecutor and that it was unlikely that guards in a detention centre would commit violent acts without legitimate reason.

The court also cast doubt on “A’s” testimony by saying that it had changed over the course of time whereas the testimony of the guards had been consistent. The judge stated that since two months had elapsed between the time the injuries were sustained and the date of the “preservation of evidence” (when the medical examination was carried out and photographs were taken), it was not possible to say for certain that the scars on “A’s” body had any connection with alleged ill-treatment by prison guards.

When “A” lodged an appeal against this judgement, he finally won a decision from the High Court to order the submission of his medical records. Ordering the detention centre to submit the medical records to the court was the only way in which “A” and his lawyer could have access to them. However, the medical records, which were drawn up by medical personnel employed by the Detention Centre, were not submitted in full: it appears that the Detention Centre only submitted documents in which potentially vital sections had been “blacked out”. The name of the doctor who examined “A” at the time of the alleged ill-treatment was also erased, making it impossible for “A” to seek a testimony from that doctor. The case is still under consideration by the High Court. Amnesty International is concerned that “A” appears to have suffered severe ill-treatment, including sexual assault. The organization is concerned that the investigations into “A”’s complaints have been wholly inadequate, and may hamper the emergence of the truth.

“B”, a Nigerian national, has been detained at the Tokyo Detention Centre since 10 February 1994. He has reportedly been subject to violence from guards on four separate occasions. The first assault happened on the second day of his detention when he claims that a guard arbitrarily decided to confiscate most of his bedding. When “B” protested, five guards allegedly ran into his cell and started punching him. He was then taken to a “protection cell”, stripped naked and subjected to further beatings all over his body, including his head and abdomen, for a period of 30 or 40 minutes. As a result of this violence, “B” claims he suffered from headaches, abdominal pains and backache as well as severe anal bleeding. He was kept in the “protection cell” for one day, followed by a ten-day period of keiheikin in another cell.

The second incident occurred in April when a prison guard refused to supply “B” with his allowance of soap and toothpaste, apparently insisting that he was only supposed to give these items to Japanese inmates. When “B” asked for verification of this rule, the guard allegedly came into his cell and slapped him in the face. Later on the same day, “B” was told by the guard that he was going to be moved into a different cell. When “B” asked for an explanation for this transfer, he alleges that the guard gestured as if to hit him. “B” raised his arm spontaneously in self-defence and pushed the guard away. At this, the guard called four other guards to take him to a “protection cell”. When he arrived there, “B” alleges that he was beaten repeatedly by the guards for around 25 minutes. He was kept in the “protection cell” for two days and then moved to another solitary cell for ten days’ keiheikin.

Shortly after this incident, “B” was transferred to another building within the detention centre. He alleges that one guard in that building repeatedly made racist verbal attacks on him by calling him a “gorilla”. He claims that when the guard called him by this name on 7 July 1994, he lost his temper and shouted back at the guard: “You stupid bastard!"

At the beginning of August, “B” discovered that he was to be punished for swearing at the guard. When he refused to agree to the punishment, saying that it was the guard who was guilty of racist insults, seven or eight guards entered “B’s” cell and took him forcibly to a “protection cell”. He claims that as soon as he entered the cell, he was punched and thumped around the head. The physical consequences of this were a broken tooth, pain in his left ear, bleeding from his right ear for two weeks, and blurred vision in his left eye. He was kept in the “protection cell” for five days, followed by seven days’ keiheikin for having shouted at the guard, and fifteen days’ keiheikin for refusing to obey instructions. “B” claims that a further assault happened on 19 December 1994 when a prison guard kicked him in the groin.

“B” has attempted to have his complaints of ill-treatment considered by the courts, with little success. In his case, “preservation of evidence” was achieved on 1 November 1994 when an independent doctor gave him a thorough medical examination and wrote an “expert statement” testifying to a number of physical scars and injuries. These included the recent loss of a tooth, bruising on his knees, and blurred vision in his left eye.

The Tokyo Detention Centre refused to comply with two successive Tokyo District Court requests to submit the medical records they hold on “B” for court examination. It was only upon the court’s third request that the detention centre finally submitted the documents. However, “B’s” medical records were presented in a similar form to “A’s”: large sections of the records had been blacked out. In “B’s” case, however, the court ruled that the blacked-out portions of the records should also be revealed. Gradually the full contents of the documents were made available to the court, including the name of the examining doctor.

The Detention Centre also sought to present three “witnesses” to the court who, according to “B”, had not been present at the scene of the incidents. It was only after “B” made a formal objection that the Detention Centre allowed other witnesses -- guards present at the scene of the incident -- to testify.

Despite the fact that great pains were taken to preserve evidence, the final outcome was that “B” lost the case. The reasons given for this judgement were that the testimony of the detention officials was more credible than “B’s” testimony since the state of his injuries was not fully recorded in his medical documents and the independent doctor’s “expert testimony” did not necessarily prove that his injuries were the result of the alleged violence. The court also ruled that there was insufficient evidence to prove that “B” had been called a “gorilla” and found that, even if he had been called by this name, this in itself was not something that could be punished. The judge reportedly said:

-

“It cannot be proved whether or not the detention official called the plaintiff a “gorilla”. Whatever the truth of the matter, while such behaviour should be criticised for being improper, this in itself does not mean that such behaviour should be branded illegal”

“B” is not satisfied with this judgement and, like “A”, has appealed for reconsideration by a higher court.

Convicted of drug-trafficking, Kevin Mara, a national of the United States of America, began serving a four-and-a-half year prison sentence at Fuchu Prison, Tokyo, in March 1993 and since then has become a victim of Fuchu’s harsh regime and arbitrary rules. Ill-treatment in prison has led Mara to take the unusual step of bringing a lawsuit against the state claiming compensation of 10 million yen (about US$90,000).

Fuchu Prison: main entrance.

It appears from Kevin Mara’s testimonies that under one of the rules of Fuchu Prison, prisoners must keep their eyes closed at the meal table until everyone has taken their seat. Mara claims that on 20 June 1993, he opened his eyes prematurely because he heard somebody calling his name. He was rebuked loudly by a prison guard for violating the rule and punished with ten days’ solitary confinement.

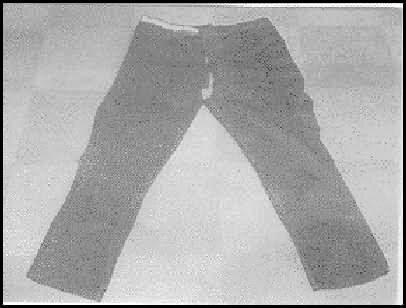

Just after this period of punishment began, however, Kevin Mara was accused by another guard of throwing a book. He claims that as further punishment, he was forced to lie face down while eight prison officers pinned him down, stripped him naked and secured his hands in leather handcuffs. The handcuffs were attached to a leather belt around his waist which was pulled so tight that he could hardly breathe. He was kept in these handcuffs for 20 hours and transferred to a hogobo (“protection cell”) for two days. While in the “protection cell” he was made to wear a strait-jacket and trousers with a slit cut in the seat for defecation.

Trousers with a slit cut in the seat, typical of those worn by prisoners in “protection cells”.

According to Ministry of Justice regulations, hogobo should only be used when it is judged inappropriate to detain a prisoner in a normal cell. Officially, the function of hogobo is to protect prisoners who are at risk of hurting themselves or other inmates, or to detain those who attempt to escape, cause damage to prison facilities, or cause a noisy disturbance and refuse to follow instructions. It is unclear in what way Kevin Mara’s behaviour fell into any of these categories. Amnesty International is concerned that in his case, the “protection cell” was used as a form of arbitrary punishment. Indeed, Mara’s case is only one of a number of recent instances brought to the attention of Amnesty International where hogobo have been used in this way as an improper form of punishment.

On 14 December 1995, Kevin Mara fell foul of the prison rules once again while working in a prison workshop. A prison guard noticed him look out of the window, apparently an infringement against prison rules, as he raised his hand to scratch his cheek. Although Mara apologized, he was made to stand facing the wall. Surprised at this harsh punishment, Mara muttered “crazy” under his breath. The guard’s reaction was to mete out a further punishment of 15 days’ solitary confinement.

A further incident occurred on 13 February 1996 when Mara wet his hair to smooth it down after a night’s sleep. He was accused of washing his hair outside the stipulated bathing time and given five days’ solitary confinement.

An accumulation of these punishments eventually led Mara to apply for legal representation from the Japanese Federation of Bar Associations in preparation for bringing a lawsuit against the state. He has indicated that his aim in bringing this case is not only to claim redress for his own ill-treatment, but also to improve conditions for others in the prison who do not dare to complain for fear of suffering a further deterioration in their own prison conditions. The proceedings for Mara’s state compensation case began in July last year, and since then his conditions of detention appear to have worsened.

Following Kevin Mara’s complaints the Fuchu Prison authorities have placed him into “strict solitary confinement”: he is forced to sit alone in the same position in the middle of his cell where he has to work for 40 hours a week making shopping bags. His work remuneration has also been reduced to about 900 yen per month (about US$9.00) - while other prisoners in Fuchu receive around 3000 yen. His food ration has been cut and he is allowed 30 minutes’ outside exercise only two or three times per week. Kevin Mara has been living under these conditions for over a year.

It is customary for prisoners in Japan to be granted the chance to apply for parole after they have served one-third of their sentence. In practice, foreign prisoners are generally allowed to apply after having served half their sentence. It is thought that Mara’s previous punishments are being used by the prison authorities as evidence that he is “unrepentant” of his crime and is therefore not eligible to apply for parole. Mara’s lawyers believe it is highly unlikely that he will be allowed to apply while he continues to appeal against his ill-treatment. Kevin Mara’s complaint has yet to be considered by a court. He is due for release in December 1997.

“I love Japanese culture and was treated very kindly by many Japanese people before I went into prison....But I have been really saddened by the things that happened to me in that prison. I don’t want my experiences in prison to lead me to hate Japan.” BD, statement made in detention

BD arrived in Japan in April 1992. In November of the same year he was arrested and charged with causing physical injury. He was tried, found guilty, and sentenced to four years’ imprisonment which he served in Fuchu Prison, Tokyo. BD claims that he suffered an intolerable degree of ill-treatment and racial abuse in Fuchu and has launched a case for state compensation claiming damages of 15 million Yen. The case is currently being considered by the Tokyo District Court.

BD claims that on 1 April 1994, he was subject to verbal abuse by a prison guard who stated that “all Iranians are liars”. When he pointed out that “Iranians are just the same as Japanese people - some are good and some are bad”, he claims he was punished with 10 days’ solitary confinement for “answering back”. On hearing about this punishment, he failed to salute the guard in the stipulated fashion, and claims that as a result of this, he was subjected to further ill-treatment: he alleges that a number of guards handcuffed him tightly in leather and metal handcuffs, pinned him down, forced a cloth bag over his head, and kicked him hard on the back and in the stomach. They then reportedly tried to pull down his trousers but were prevented from doing so because they had handcuffed him so tightly. Apparently believing that it was BD himself who was obstructing them, the guards began kicking him many times in the genital area, shouting: “Open your legs!” BD reports that he was kept in handcuffs for five hours and then confined in a “protection cell” for two days.

A second assault occurred on 14 May 1994 when BD alleges that a prison guard punched him hard on the left ear after he apparently broke a rule by standing up to brush his teeth. He claims he was placed in leather handcuffs and beaten once again. He was kept in handcuffs for nine hours and placed in a “protection cell” for two days. During this period he claims that pus oozed continuously from his left ear and he reportedly still has hearing problems as a result of the guard’s assault.

BD claims that he was assaulted, handcuffed, and confined in a “protection cell” once again on 19 July 1994 for no apparent reason.

BD decided to protest about his treatment by writing a formal letter to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. However, he claims that the prison authorities refused to allow him to send the letter. In response, BD began a hunger strike on 27 February 1995. He claims that three days later he was injected with some kind of drug without his consent, after which the prison guards physically forced food into his mouth.

Between October 1995 and July 1996, BD claims he was confined in a special cell for mentally ill prisoners. He says that during this period he was constantly troubled by the behaviour of a mentally disturbed prisoner in an adjacent cell who kept hitting himself against the wall and muttering to himself all day and all night. He believes that the prison guards kept him in these conditions in order to break his will and give up on the idea of making a formal complaint. He claims that the guards fabricated a story about him attempting to swallow a razor blade in order to justify his abnormal confinement. He was finally released from the special cell on 15 July 1995 after a prison inspector from the Ministry of Justice accepted his petition. BD filed his case for state compensation on 29 August 1997 and pre-trial investigations into his testimony as well as examinations of his physical health are currently underway. BD left Fuchu Prison on 28 January 1997 and is currently being held in the East Japan Immigration Detention Centre. An Amnesty International delegation which visited Fuchu prison in June 1997 was not allowed to discuss his case with prison officials.